Authors: Dahlia Malkhi and Pawel Szalachowski

October 19th, 2022: see an updated revision.

Synopsis

Another advantage of a DAG-based approach to BFT Consensus is enabling simple and smooth prevention of blockchain extractable value (BEV) exploits. This post describes how to integrate “Order-Fairness” into DAG-based BFT Consensus protocols to prevent BEV exploits. For more details, refer to our recent manuscript “Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) Protection on a DAG”.

The first line of BEV defense is “Blind Order-Fairness”. The idea is for users to send their transactions to Consensus parties encrypted, such that honest parties must be involved in opening the decryption key. Consensus parties commit to a blind order of transactions first, and only later open the transactions. We discuss how to leverage the DAG structure to achieve blind ordering BEV protection in a simple and efficient manner. Notably, the scheme operates without materially modifying the DAG’s underlying transport, without secret share verification, and in the happy path, it works in microseconds latency and avoids threshold encryption.

A deeper line of defense, “Time-Based Order-Fairness”, incorporates additional input on relative-ordering among batches of committed transactions. We discuss building such considerations into our scheme.

The third line of defense is “Participation Fairness” (aka “Chain Quality”), which guarantees that a chain of blocks includes a certain portion of honest contributions. As demonstrated in several previous systems, a “layered DAG” achieves certain participation equity for free, since at least a fraction of honest Consensus parties contributes in each layer.

Introduction: BEV and Order-Fairness

Over the last few years, we have seen exploding interest in cryptocurrency platforms and applications built upon them, like decentralized finance protocols offering censorship-resistant and open access to financial instruments; or non-fungible tokens. Many of these systems are vulnerable to BEV attacks, where a malicious consensus leader can inject transactions or change the order of user transactions to maximize its profit. Thus it is not surprising that at the same time we have witnessed rising phenomena of BEV professionalization, where an entire ecosystem of BEV exploitation, comprising of BEV opportunity “searchers” and collaborating miners, has arisen.

Daian et al. introduced a measure in [Flash Boys 2.0, S&P 2020] of the “profit that can be made through including, excluding, or re-ordering transactions within blocks”. The original work called the measure miner extractable value (MEV), which was later extended by blockchain extractable value (BEV) [Qin et al., S&P 2022], to include other forms of attacks, not necessarily performed by miners. [MEV-explore] estimates the amount of BEV extracted on Ethereum since the 1st of Jan 2020 to be close to $700M. However, it is safe to assume that the total BEV extracted is much higher, since MEV-explore limits its estimates to only one blockchain, a few protocols, and a limited number of detectable BEV techniques. Although it is difficult to argue that all BEV is “bad” (e.g., market arbitrage can remove market inefficiencies), it usually introduces some negative externalities like:

- Network congestion: especially on low-cost chains, BEV actors often try to increase their chances of exploiting a BEV opportunity by sending a lot of redundant transactions, spamming the underlying peer-to-peer network,

- Chain congestion: many such transactions finally make it to the chain, making the chain more congested,

- Higher blockchain costs: while competing for profitable BEV opportunities, BEV actors bid higher gas prices to prioritize their transactions, which results in overall higher blockchain costs for regular users,

- Consensus stability: some on-chain transactions can create such a lucrative BEV opportunity that it may be tempting for miner(s) to create an alternative chain fork with such a transaction extracted by them, which introduces consensus instability risks.

In this blog post, we focus on consensus-level BEV mitigation techniques. There are fundamentally two types of BEV-resistant Order-Fairness properties:

Blind Order-Fairness. A principal line of defense against BEV stems from committing to transaction ordering without seeing transaction contents. This notion of BEV resistance, referred to here as Blind Order-Fairness, is used by Heimbach and Wattenhoffer in [SoK on Preventing Transaction Reordering, 2022] and is defined as

“when it is not possible for any party to include or exclude transactions after seeing their contents. Further, it should not be possible for any party to insert their own transaction before any transaction whose contents it already been observed.”

Time-Based Order-Fairness. Another strong measure for BEV protection is brought by sending transactions to all Consensus parties simultaneously and using the relative arrival order at a majority of the parties to determine the final ordering. In particular, this notion of order fairness ensures that

“if sufficiently many parties receive a transaction tx before another tx’, then in the final commit order tx’ is not sequenced before tx.”

This prevents powerful adversaries that can analyze network traffic and transaction contents from reordering, censoring, and front-/back-running transactions received by Consensus parties. Moreover, Time-Based Order-Fairness has stronger protection against a potential collusion between users and Consensus leader/parties because parties explicitly input relative ordering into the protocol.

Time-Based Order-Fairness is used in various flavors in several recent works, including [Aequitas, CRYPTO 2020], [Pompē, OSDI 2020], [Themis, 2021], Wendy Grows Up [FC 2021] and [Quick Order Fairness, FC 2022], We briefly discuss some of those protocols later in the post.

Another notion of fairness found in the literature, that does not provide Order-Fairness, revolves around participation fairness:

Participation Fairness. A different notion of fairness aims to ensure censorship-resistance or stronger notions of participation equity. Participation equity guarantees that a chain of blocks includes a certain portion of honest contribution (aka “Chain Quality”). Several BFT protocols address Participation Fairness, including [Prime, IEEE TDSC 2010], [Fairledger, 2019], [HoneyBadger, CCS 2016], and many others. In layered DAG-based BFT protocols like [Aleph, AFT 2019], [DAG-Rider, PODC 2021], [Tusk, 2021], [Bullshark, 2022], Participation Fairness comes essentially for free because every DAG layer must include messages from 2F+1 participants. It is worth noting that participation equity does not prevent a corrupt party from injecting transactions after it has already observed other transactions, nor a corrupt leader from reordering transactions after reading them, violating both Blind and Time-Based Order-Fairness.

Outline

We proceed to describe how to build Order-Fairness into DAG-based BFT Consensus for the partial synchrony model, focusing on preventing BEV exploits. The rest of this post is organized as follows:

-

The next section provides a Quick refresher on DAG-based BFT Consensus and Fin; We refer the reader to a previous post on DAG-based BFT Consensus and Fin for further details, and to a list at its bottom for further reading on DAG-based BFT Consensus.

-

Following is a section that discusses Order-then-Reveal: On Achieving Blind Order-Fairness. It contains two strawman “order-commit first, reveal later” implementations, Order-then-Reveal with Threshold Cryptography, Order-then-Reveal with Verifiable Secret-Sharing (VSS).

-

It is followed by the introduction of Fino: Optimistically-Fast Blind Order-Fairness without VSS. Fino achieves the best of both worlds, seamless blind ordering of threshold cryptography with the low latency of secret sharing.

-

The next section reports Threshold Encryption vs Secret Sharing micro-benchmarks.

-

The last section adds a discussion on Achieving Time-Based Order-Fairness.

A recent ArXiv manuscript provides more detail and rigor, see “Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) Protection on a DAG”.

Quick refresher on DAG-based BFT Consensus and Fin

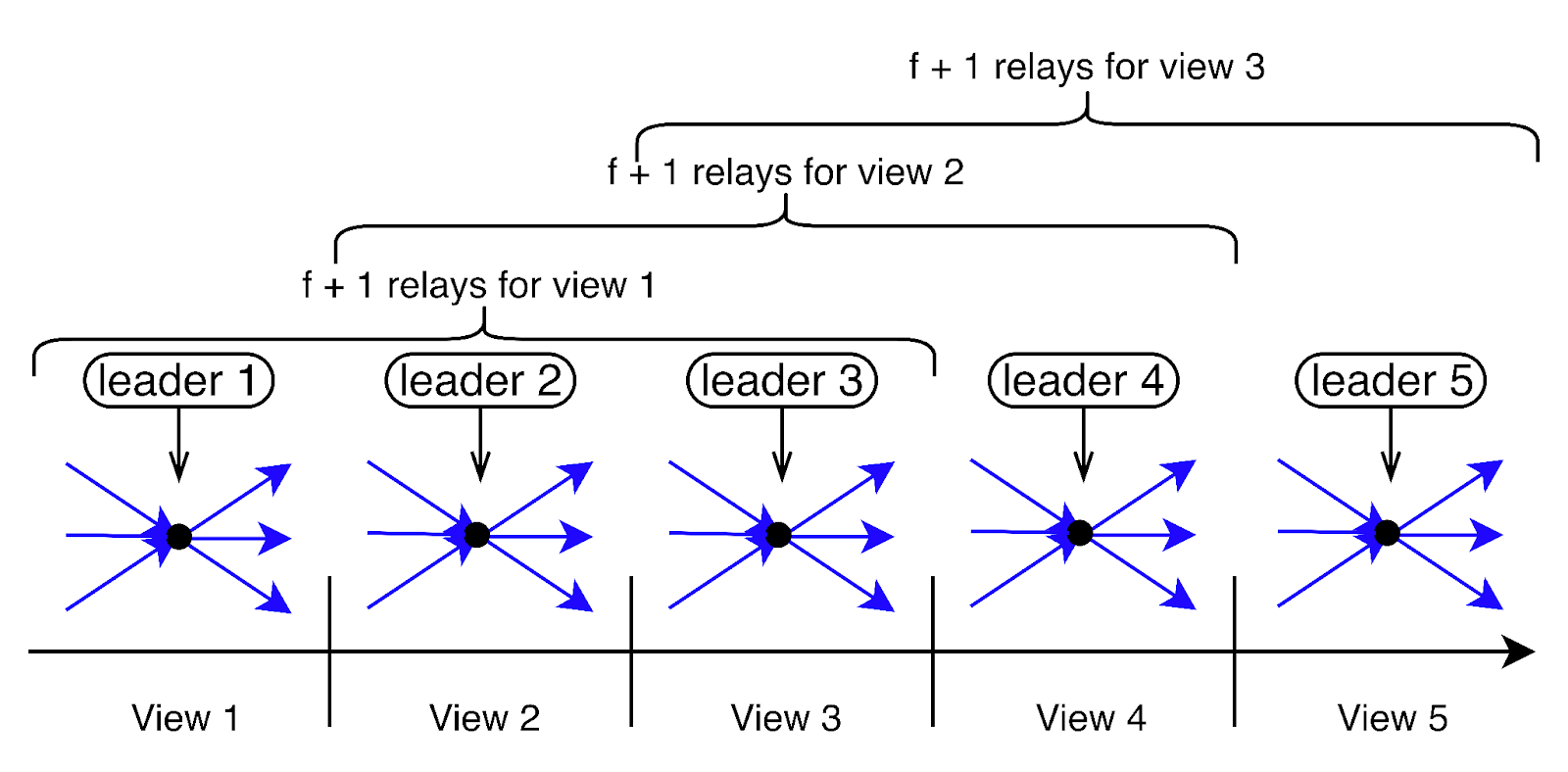

DAG-based BFT Consensus revolves around a broadcast transport that guarantees message Reliability, Availability, Integrity, and Causality.

In a DAG-based BFT Consensus protocol, a party packs transaction digests into a block, adds references to previously delivered (defined below) messages, and broadcasts a message carrying the block and the causal references to all parties. When another party receives the message, it checks whether it needs to retrieve a copy of any of the transactions in the block and in causally preceding blocks. Once it receives a copy of all transactions in the causal past of a block it can acknowledge it. When 2F+1 acknowledgments are gathered, the message is “delivered” into the DAG.

One implementation of reliable broadcast is due to [Bracha, 1987]. Each party sends an echo message upon receiving a new transaction. Each party, after receiving 2F+1 echoes (or F+1 ready votes), can issue and broadcast a ready vote. A party delivers the transaction when 2F+1 ready votes are received. Another implementation used in several earlier systems, e.g., [Reiter and Birman, 1994] and [Cachin et al., 2001], employs threshold cryptography.

Several recent systems, e.g., Aleph, Narwhal-HS, DAG-Rider, Tusk, and Bullshark, construct DAG transports in a layered manner, demonstrated excellent network utilization and throughput. In a layered DAG, each party can broadcast one message in each layer carrying 2F+1 references to messages in the preceding layer. We note that layering is not required for any of the methods described below but has important benefits on performance and Participation Fairness.

Given the strong guarantees of a DAG transport, Consensus can be embedded in the DAG quite simply, for example, using [Fin, 2022]. Briefly, Fin works as follows:

-

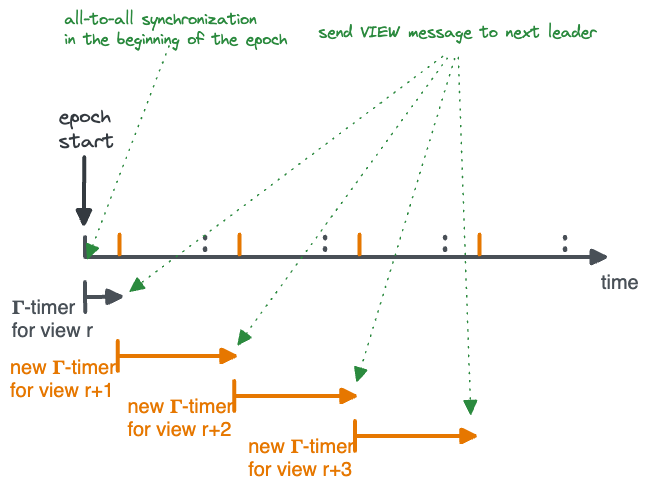

Views. The protocol operates in a view-by-view manner. Each view is numbered, as in “view(r)”, and has a designated leader known to everyone.

-

Proposing. When a leader enters a new view(r), it sets a “meta-information” field in its coming broadcast to

r. A leader’s message carryingr(for the first time) is interpreted asproposal(r). Implicitly,proposal(r)suggests to commit to the global ordering of transactions all the blocks in the causal history of the proposal. -

Voting. When a party sees a valid leader proposal, it sets a “meta-information” field in its coming broadcast to

r. A party’s message carryingr(for the first time) followingproposal(r)is interpreted asvote(r). -

Committing. Whenever a leader proposal gains F+1 valid votes, the proposal and its causal history become committed.

-

Complaining. If a party gives up waiting for a commit to happen in view(r), it sets a “meta-information” field in its coming broadcast to

-r. A party’s message carrying-r(for the first time) is interpreted ascomplaint(r). Note, a message by a party carryingrthat causally follows acomplaint(r)by the party, if exists, is not interpreted as a vote. -

View change. Whenever a commit occurs in view(r) or 2F+1

complaint(r)are obtained, the next view(r+1) is enabled.

We refer the reader to a previous post on DAG-based BFT Consensus and Fin for further details, and to a list at its bottom for further reading on DAG-based BFT Consensus.

Order-then-Reveal: On Achieving Blind Order-Fairness

The first line of defense against BEV is to keep transaction information hidden until after a commit is delivered “blindly”. This prevents any party from observing the contents of transactions until the ordering has been committed, hence satisfying Blind Order-Fairness.

To order transactions blindly, users choose a symmetric key to encrypt each transaction and broadcast the transaction encrypted to Consensus parties.

Order-then-Reveal is implemented using three abstract functionalities to hide and open the transaction key (“tx-key”) itself: Disperse(tx-key), Reveal(tx-key), Reconstruct(tx-key). In Disperse(), the user shares tx-key with parties such that a threshold greater than F of the parties is required to participate in reconstruction. In Reveal(), parties retrieve F+1 shares. Parties must withhold revealing decryption shares until after they observe the transaction’s ordering committed. In Reconstruct(), parties produce a unique reconstruction of tx or reject it.

The challenge with Blind Order-Fairness is enforcing a unique outcome once an ordering has been committed.

Strawman 1: Order-then-Reveal with Threshold Cryptography

It is straight-forward to support blind ordering using threshold encryption, such that a public encryption “E()” is known to users and the private decryption “D()” is shared (at setup time) among parties.

For each tx, a user chooses a transaction-specific symmetric key tx-key and sends tx encrypted with it. To Disperse(tx-key), the user attaches E(tx-key), the transaction key encrypted with the global threshold key. Once a transaction tx’s ordering is committed, Reveal(tx-key) is implemented by every party generating its decryption share for D(tx-key), piggybacked on the DAG broadcast that causally follows the commit. Some threshold cryptography schemes allow to verify that a party is contributing a correct decryption share. A threshold of honest parties can always succeed in Reconstruct(tx-key) and try applying it to decrypt tx, hence by retrieving F+1 threshold shares, a unique outcome is guaranteed.

The main drawback of threshold cryptography is that share verification and decryption are computationally heavy. It takes an order of milliseconds per transaction in today’s computing technology, as we show later in the article (see Performance notes).

Strawman 2: Order-then-Reveal with Verifiable Secret-Sharing (VSS)

Another way for users to Disperse(tx-key) is [Shamir’s secret sharing scheme, CACM 1979]. A sharing function “SS-share(tx-key)” is employed by users to send individual shares to each Consensus party, such that F+1 parties can combine shares via “SS-combine()” to reconstruct tx-key.

Combining shares is three orders of magnitude faster than threshold crypto and takes a few microseconds in today’s computing environment (see Performance notes). However, it is far less straight-forward to build Reveal() and Reconstruct() with secret-sharing on a DAG:

- When a transaction ordering becomes committed, revealing F+1 shares is not guaranteed even during periods of synchrony.

In particular, there may be only F+1 honest parties with shares but F of them are “left behind” when the DAG grows.

Although unlikely, this situation could linger indefinitely simply due to the slowness of honest parties,

and there would be an insufficient number of shares in the DAG to decrypt the transaction.

In each layer of a DAG, participation by 2F+1 parties is guaranteed, but unfortunately:

- F of them could be bad and pretend they don’t have shares,

- F of them do not have shares,

- Only one party out of F+1 honest parties that have shares participates and reveals its share.

- Conversely, if more than F+1 shares are revealed, combining different subsets could yield different “decryption” tx-keys if the user is bad. Hence, a transaction decryption might not be uniquely determined.

One solution is to employ a VSS scheme, allowing F+1 parties to construct missing shares on behalf of other parties, as well as to verify that shares are consistent, This enables the integration of secret sharing into the DAG broadcast protocol, but it requires modifying the DAG transport.

A DAG transport with Verifiable Secret Sharing. To ensure that a transaction that has been delivered into the DAG can be deciphered, a party should not acknowledge a message unless it has retrieved its own individual shares for all the transactions referenced in the message and its causal past.

For example, integrating VSS inside Bracha’s reliable broadcast, when a party observes that it has missed a share for a transaction referenced in a message (or its causal past), it initiates VSS share recovery before sending a ready vote for the message. This guarantees that a fortiori, after blindly committing to an ordering for the transaction, messages from every honest party reveal shares for it.

The overall communication complexity incurred in VSS on the user sharing a secret and on a party recovering a share has dramatically improved in recent years:

- VSS can be implemented inside the asynchronous echo broadcast protocol in n3 communication complexity using Pederson’s original two-dimensional polynomial scheme [Non-Interactive Polynomial Commitments, CRYPTO 1991].

- Kate et al. introduced a VSS scheme with n2 communication complexity [Constant-Size Polynomial Commitments, ASIACRYPT 2010], later utilized for AVSS by Backes et al. [eAVSS-SC, CT-RSA 2013].

- Basu et al. improved to linear (n) communication complexity [T3P, CCS 2019].

Despite the vast progress in VSS schemes, there remain a number of challenges. The main hurdle is that when a message is delivered with 2F+1 acknowledgments, parties may need to recover their individual shares when they reference it in order to satisfy the Reliability property of DAG broadcast. As noted above, the most efficient VSS scheme requires linear communication and each share carries linear size information for recovery. Implementing VSS (e.g., due to Kate et al.) requires non-trivial cryptography. Last, as noted above, in the DAG setting this requires integrating a share-recovery protocol in the underlying transport.

Fino: Optimistically-Fast Blind Order-Fairness without VSS

Can we have the best of both worlds, seamless Reveal/Reconstruct of threshold cryptography with the low latency of secret sharing?

Enter Fino, an embedding of Blind Order-Fairness in DAG-based BFT Consensus that leverages the DAG structure to completely forego the need for share verification during dispersal, works with (fast) secret-sharing during steady-state, and falls back to threshold crypto during a period of network instability. That is, Fino works without VSS and is optimistically fast. Importantly, in Fino the DAG transport does not need to be materially modified. During periods of synchrony, transactions that were committed blindly to the total order will be opened within three network latencies following the commit.

To avoid verifying shares during Disperse (costly), we borrow a key insight from AVID-M (see DispersedLedger), namely verifying that the (entire) sharing was correct post-reconstruction (cheap). Importantly, even when reconstruction using revealed shares happens to be successful, if either the slow or the fast sharing was incorrect and fails post-reconstruction verification, the transaction is simply rejected. More specifically, this works as follows. After ordering a batch of transactions is committed and F+1 shares are revealed, each party re-encodes opened transactions using both secret-sharing and threshold encryption and compares with two hashes: one is a Merkle-tree root hash of the SS shares, the second is the threshold-encryption hash of the symmetric key. If there is a mismatch, the transaction is rejected.

To build Fino, we wanted a simple baseline DAG-BFT algorithmic foundation, so we chose [Fin, 2022], hence the name Fino – Fin plus BEV-resistant Order-Fairness. The advantage is Fin’s simplicity of exposition, the lack of rigid layer structure, and because in Fin messages can be inserted into the DAG independently of Consensus steps or timers, but Fino can possibly be built on other DAG-BFT systems.

An important feature of the DAG-based BFT approach, which Fino preserves while adding blind ordering, is zero message overhead. Additionally, Fino never requires the DAG to wait for input that depends on Consensus steps/timers.

Overview of Fino

To order transactions tx blindly in Fino, a user first chooses (as before) a transaction-specific symmetric key tx-key and encrypts tx with it.

Disperse(tx-key) is implemented in two parts. First, a user applies SS-share(tx-key) to send parties individual shares of tx-key. Second, as a fallback, it sends parties E(tx-key).

Once a transaction tx’s ordering is committed, Reveal(tx-key) has a fast track and a slow track. In the fast track, every party that holds an SS-share for tx-key reveals it piggybacked on the DAG broadcast that causally follows the decision. A party that doesn’t hold a share for tx-key reveals a threshold key decryption share, similarly piggybacked on a normal DAG broadcast that causally follows the commit. In the slow track, parties give up on waiting for SS-shares and reveal threshold key decryption shares even if they already revealed SS-shares.

It is left to form agreement on a unique decryption. Luckily, we can embed deterministic agreement about how to decipher transactions into the DAG with zero extra messages and no waiting for Consensus steps/timers. Parties simply interpret their local DAGs to arrive at unanimous deterministic decryption.

More specifically, views, proposals, votes, and complaints in Fino are the same as Fin. The differences between Fino and Fin are as follows:

Share revealing. When parties observe that a transaction tx becomes committed, their next DAG broadcast causally following the commit reveals shares of the decryption key tx-key in one of two forms: a party that holds a share for SS-combine(tx-key) reveals it, while a party that doesn’t hold a share for SS-combine(tx-key) or give up waiting reveals a threshold share for D(tx-key).

TX Opening.

When a new leader enters view(r+1), it emits a proposal proposal(r+1) as usual.

However, when the proposal becomes committed,

it determines a unique decryption for every transaction tx in the causal past of proposal(r+1) that satisfies:

txis committed but not yet opened,txhas F+1 certified shares revealed in the causal past ofproposal(r+1),

Note that above, tx could be from views earlier than view(r) if they haven’t been opened already.

The unique opening or rejection of tx based on f+1 revealed shares is explained above.

A Note on Happy-path Latency. During periods of stability, there are no complaints about honest leaders by any honest party. If tx is proposed by an honest leader in view(r), it will receive F+1 votes and become committed within one network latency. Within one more network latency, every honest party will post a message containing a share for tx. Out of 2F+1 shares, either F+1 are SS-combine() shares or D() shares. Thereafter, whenever a leader proposal references 2F+1 shares commits (in a layered DAG, the leader after next will), everyone will be able to apply Reconstruct(tx-key) and either open tx or reject it. In a happy path, opening happens three network latencies after a commit: one for revealing shares, one for a leader proposal following the shares, and one to commit the proposal.

A Note on Share Certification. In lieu of share verification information in SS-share(), a sender needs to certify shares so that parties cannot tamper with them.

The sender combines all shares in a Merkle tree, certifies the root, and sends with each share a proof of membership (i.e., a Merkle tree path to the root); parties need to check only one signature when they collect shares for reconstruction. After reconstruction, parties can re-encode the Merkle tree and verify it was generated correctly.

To verify share-generation in the slow path, the sender additionally certifies E(tx-key), the threshold encryption of symmetric key used for encrypting the transaction.

Scenario-by-scenario Walkthrough

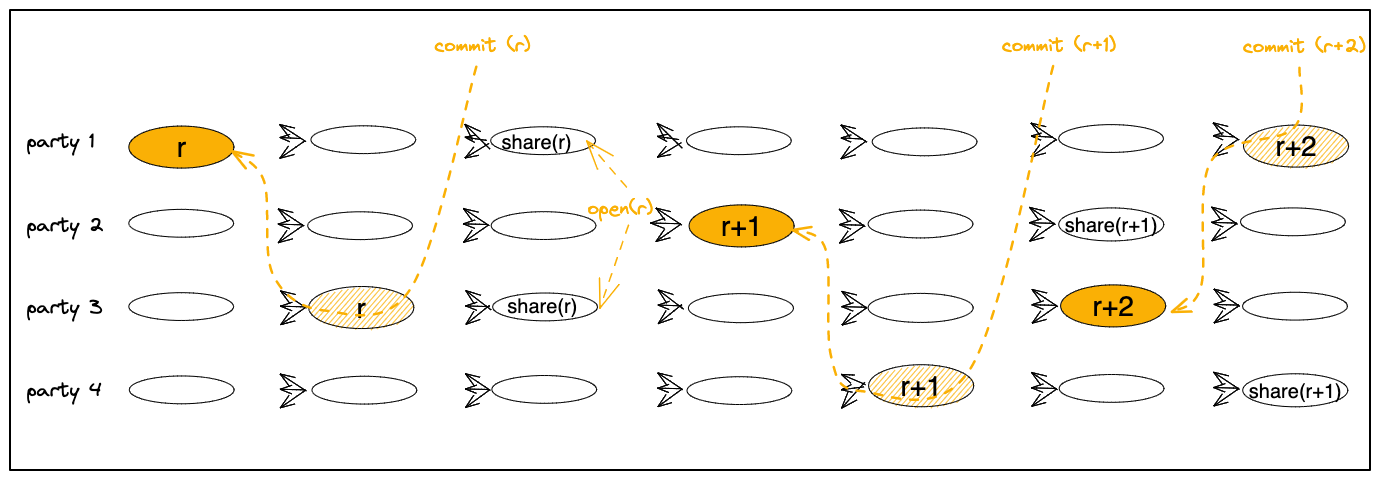

Happy-path scenario.

Figure 1 below depicts a scenario with three views, r, r+1, and r+2.

Each view enables the next view via F+1 votes.

The scenario depicts proposal(r+1) becoming committed. The commit uniquely determines how to open transactions from proposal(r),

whose shares have been revealed in the causal past of proposal(r+1).

Differently, proposal(r+2) is sent before delivering F+1 shares of transactions from proposal(r+1).

Therefore, proposal(r+2) becomes committed without opening pending committed transactions from view(r+1).

Figure 1:

Commits of proposal(r) and proposal(r+1), followed by share revealing opening proposal(r) tx’s.

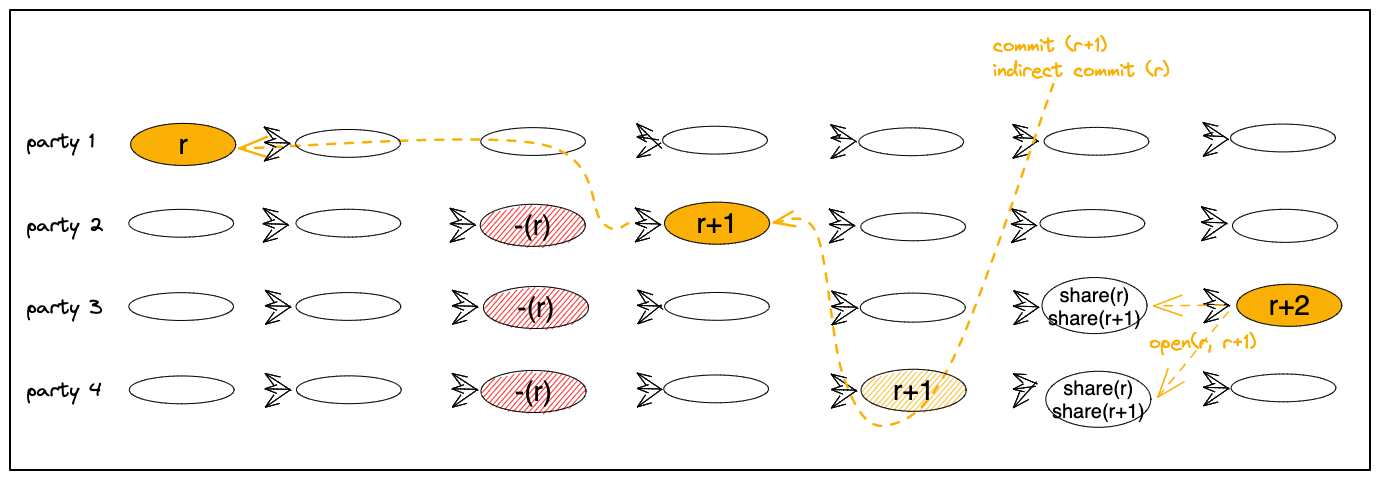

Scenario with a slow leader. A slightly more complex scenario occurs when a view expires because parties do not observe a leader’s proposal becoming committed and they broadcast complaints. In this case, the next view is not enabled by F+1 votes but rather, by 2F+1 complaints.

When a leader enters the next view due to 2F+1 complaints, the proposal of the preceding view is not considered committed yet. Only when the proposal of the new view becomes committed does it indirectly cause the preceding proposal (if exists) to become committed as well.

Figure 2 below depicts three views, r, r+1, and r+2.

Entering view(r+1) is enabled by 2F+1 complaints about view(r).

When proposal(r+1) itself becomes committed, it indirectly commits proposal(r) as well.

Thereafter,

parties reveal shares for all pending committed transactions, namely, those in both proposal(r) and proposal(r+1).

Those shares are in the causal past of proposal(r+2).

Hence, when proposal(r+2) will commit, a unique opening will be induced.

Figure 2:

A commit of proposal(r+1) causing an indirect commit of proposal(r), followed by share revealing of both.

Threshold Encryption vs Secret Sharing

Threshold encryption and secret sharing provide slightly different properties

when combined with a protocol like Fino.

We have implemented both schemes and compared their performance. For

secret sharing, we implemented the

[Shamir’s scheme, CACM 1979],

while for threshold encryption we implemented a scheme by

Shoup and Gennaro [TDH2, EUROCRYPT 1998].

First, we investigated the computational overhead that these schemes introduce.

For the presentation, we selected the schemes with the most efficient

cryptographic primitives we had access to, i.e., the secret sharing scheme was

implemented using the

[Ed25519 curve, J Cryptogr Eng 2012],

while TDH2 is using

[Ristretto255, 2020]

as the underlying prime-order group. Performance for both schemes is presented in the

setting where 6 shares out of 16 are required to recover the plaintext.

| Scheme | Encrypt |

ShareGen |

Verify |

Decrypt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold, TDH2-based | 311.6μs | 434.8μs | 492.5μs | 763.9μs |

| Secret-sharing | 52.7μs | - | 2.7μs | 3.5μs |

The results are presented in the table as obtained on an Apple M1 Pro. Encrypt

refers to the overhead on the client-side while ShareGen is the operation of

deriving a decryption share from the TDH2 ciphertext by each party (this

operation is absent in the SSS-based scheme). In TDH2 Verify verifies whether

a decryption share matches the ciphertext, while in the SSS-based scheme it only

checks whether a share belongs to the tree aggregated by the Merkle root

attached by the client. Decrypt recovers the plaintext from the ciphertext and

the number of shares. As demonstrated by these measurements, the SSS-based scheme is much more

efficient. In our Consensus scenario, each party processing a TDH2 ciphertext

would call ShareGen once to derive its decryption share, Verify k-1 times

to verify the threshold number of received shares, and Decrypt once to obtain

the plaintext. Assuming k=6, the total computational overhead for a single

transaction would be around 3.7ms of the CPU time. With the secret sharing

scheme, the party would also call Verify k-1 times and Decrypt once, which

requires only 17μs of the CPU time.

Besides the higher performance overhead, TDH2 requires a trusted setup, but the scheme also provides some advantages over secret sharing. For instance, with a TDH2 ciphertext sent only to a single party and the network will be able to recover the plaintext. An SSS-based requires the client to send shares directly to multiple parties. Meanwhile, waiting for the network to receive shares for a transaction, the transaction occupies buffer space on parties’ machines and would need to be either expired by the parties (possibly violating liveness) or kept in the state forever (possibly introducing a denial-of-service vector). Moreover, SSS requires a trusted channel between clients and parties, which is not required by TDH2 itself. Finally, as described in Fino, the subset of shares used for decrypting a transaction requires a consensus decision.

Achieving Time-Based Order-Fairness

Fino achieves Blind Order-Fairness by deterministically ordering encrypted transactions and then, after the order is final, decrypting them. The deterministic order can be enhanced by sophisticated ordering logic present in other protocols. In particular, Fino can be extended to provide Time-Based Fairness additionally ensuring that the received transactions are not only unreadable by parties, but also their relative order cannot be influenced by malicious parties.

For instance, [Pompē, OSDI 2020] proposes a property called “Ordering Linearizability”:

if all correct parties timestamp transactions tx, tx’ such that tx’ has a lower timestamp than tx by everyone, then tx’ is ordered before tx.

It implements the property based on an observation that if parties exchange transactions associated with their receiving timestamps, then for each transaction its median timestamp, computed out of 2F+1 timestamps collected, is between the minimum and maximum timestamps of honest parties.

Fino can be easily extended by the Linearizability property offered by Pompē and the final protocol is similar to the Fino with Blind Order-Fairness (see above) with only one modification. Namely, every time a new batch of transactions becomes committed, parties independently sort transactions by their aggregate (median) timestamps.

More generally, Fino can easily incorporate other Time-based Fairness ordering logic. Note that in Fino, the ordering of transactions is determined on encrypted transactions, but time ordering information should be open. The share revealing, share collection, and unique decryption following a committed ordering are the same as presented previously. The final protocol offers much stronger properties since it not only hides payloads of unordered transactions from parties, but also prevents parties from reordering received transactions.

Other protocols providing Time-based Order-Fairness include [Aequitas, CRYPTO 2020] which defines “Approximate-Order Fairness”:

if sufficiently many parties receive a transaction tx more than a pre-determined gap before another transaction tx’, then no honest party can deliver tx’ before tx.

The authors prove that it is impossible to achieve this property under Condorcet scenarios, although, in practice, it might hold in most fairness-sequencing protocol executions. Then, they propose a relaxed definition of “Batch-Order Fairness”:

if sufficiently many (at least ½ of the) parties receive a transaction tx before another transaction tx’, then no honest party can deliver tx in a block after tx’,

and a protocol achieving it.

[Themis, 2021] is a more efficient protocol realizing “Batch-Order Fairness”, where parties do not rely on timestamps (as in Pompē) but only on their relative transaction orders reported. Themis can also be integrated with Fino, however, to make it compatible this design requires some modifications to Fin’s underlying DAG protocol. More concretely, Themis assumes that the fraction of bad parties cannot be one quarter, i.e., F out of 4F+1. A leader makes a proposal based on 3F+1 out of 4F+1 transaction orderings (each reported by a distinct party). Therefore, we would need to modify the DAG transport so that parties references preceding messages from a quorum greater than three-quarters of the system (rather than two-thirds). message.

Other forms of Time-Based Order-Fairness appear in other recent works, including Wendy Grows Up [FC 2021] which introduced “Timed Relative Fairness”:

if there is a time t such that all honest parties saw (according to their local clock) tx before t and tx’ after t , then tx must be scheduled before tx’.

and [Quick Order Fairness, FC 2022], which defined “Differential-Order Fairness”:

when the number of correct parties that broadcast tx before tx’ exceeds the number that broadcast tx’ before tx by more than 2F + κ, for some κ ≥ 0, then the protocol must not deliver tx’ before tx (but they may be delivered together),

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Soumya Basu, Christian Cachin, Mahimna Kelkar and Oded Naor for the comments that helped improve this post.